When it comes to business process improvement, the concept of best practices is enticing. Although the concept certainly has its place, there are problems with how it is applied in practice.

First, the term best practices has at least two major and totally different definitions, and second, in many areas of business, there is not generally agreement on what are the best practices.

Two Definitions of Best Practices

As just noted, practitioners often use the term best practices in two completely different ways, and it is important to understand the context. The first is in the sense of “the best way to do something.” The current definition in Wikipedia is typical:

A best practice is a technique, method, process, activity, incentive, or reward which conventional wisdom regards as more effective at delivering a particular outcome than any other technique, method, process, etc. when applied to a particular condition or circumstance.

For example, conventional wisdom might define a best practice in recruiting new employees as establishing a formal employee-referral program, as this channel often results in the highest quality candidates, lowest cost of recruiting, and best retention rates.

The second definition, which we see occasionally, has to do with best practices in the sense of metrics. Here, business leaders use the term not to describe the best way to do something, but the best performance that is attained among peers against some metric. For example, again using the recruiting example, the median retention rate after six months for newly-hired nurses in US hospitals might be 75%. But the “best practice” (i.e. the retention rate achieved by the best performing hospitals) might be 92%.

So, when someone asks about the best practices for recruiting you have to ask, “Do you mean what are the best policies, procedures, and practices in recruiting, or do you mean, what is the best performance against some metrics by the organizations that are the most successful in recruiting?”

Best Practices Are Not Always Universally Applicable

For now, let’s go with the first definition. Are there really ways of doing business that are generally accepted as best? In some cases, yes, but in many cases no.

Let’s illustrate with an experience we had several years ago with a prospect for our business process improvement consulting services. The prospect was a mid-size manufacturing firm. Our first meeting with the selection committee went quite well. We outlined our approach to business process re-engineering and described some case studies for similar projects.

Based on the committee’s recommendation, we then scheduled a one-on-one meeting with the President. During that meeting, he asked, “Where do you compare our practices against industry best-practices and what is your source for those best practices?” We indicated that there are a number of professional societies that are good sources for best practices, such as APICS, which is the generally accepted source for best practices in materials management. In addition, we would use our own knowledge and experience from other clients as to where this organization could be viewed as having a need for improvement.

In a debriefing session afterward, the VP of Information Systems, who was sitting in on the meeting, confirmed that the President didn’t feel our approach to best practices was strong enough.

The VP was sympathetic and still hoped that we could win the deal. So we shared with him why we felt that the President’s emphasis on best practices might be misplaced.

We illustrated with the example of “significant part numbering.” We had learned earlier that this company was formatting its part numbers by letting each digit or character of the product item number stand for something meaningful. For example the first two characters might indicate the product family, the second two might indicate the sub-family, the third digit might indicate the size of the product, the fourth digit might indicate the material, and so forth.

The VP said, “Yes, that’s right. We’ve always done it that way.”

“That’s not a best practice,” we replied.

“Really, says who?” asked the VP.

“APICS,” we said. “APICS has been preaching against the use of significant part numbers since the mid-197o’s. The reason is that it creates all kinds of problems. Invariably, as companies grow and their product portfolio changes, they outgrow their numbering schemes. Either the part number becomes extraordinarily long, or people just give it up. If you want to describe the product, use other fields on the item master. You don’t need to make the part number work that hard. ”

We continued, “Now, here’s the point. Despite the fact that significant part numbers are not a best practice, if we do this project, we’re probably not going to try to change your part-numbering scheme. You’ve got it, and it’s probably too difficult to change at this time, even though it’s not a best-practice. A good consultant will look at what you are doing and will weigh the pro’s and con’s of changing it. That’s how you’ve got to apply so-called best practices.”

You can’t just go to some database of best practices and say, here’s what you should be doing. You need to apply judgment, based on experience.

Of course, this approach does not scale for large consulting firms, who like to staff business improvement projects with a many junior associates. It’s much easier to give them a database of best practices and tell them, find out if the client is doing these. If not, recommend they do them. It’s much harder to go in and evaluate the situation according to the client’s specific situation.

Best Performance Not Universally Attainable

There are also problems with the second definition of best practices: the best performance attained among peers against some metric. This problem is common to all benchmarking exercises: defining the peer group and identifying the reasons for superior performance.

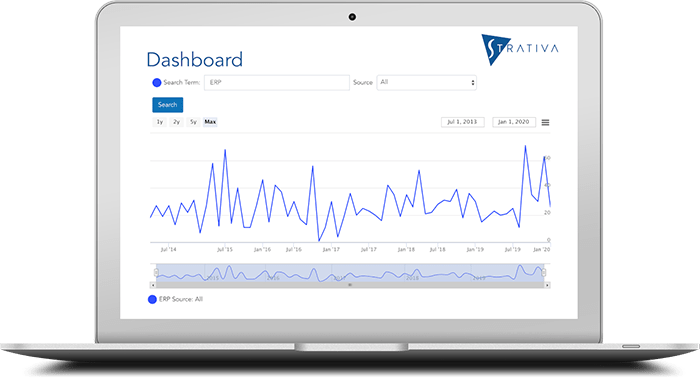

For example, our sister IT research firm, Computer Economics, publishes metrics on IT spending and IT staffing ratios. In addition, we provide a IT spending benchmarking service where we calculate the client’s metrics, compare them to our published ratios, and provide our analysis of the gaps in performance.

Invariably, there is almost always a significant amount of judgment that we need to apply in our analysis. For example, just recently, a benchmark client (a public utility) showed that the number of users per IT help desk staff member was near the 25th percentile in comparison with other organizations of this size. The number of PCs supported by each help desk staff member showed similar sub-standard performance.

However, when interviewing the client, we discovered that the agency had an online permitting system that builders and developers used to submit permit applications. The IT help desk, which normally would only serve internal users, was also serving the general public as users of this application. Knowing our data, we were sure that this was not the case with the majority of our survey respondents in the utilities industry.

So this client was well under what we would consider a “best performance” (something at or above the 75th percentile for this metric). But when we factored in the percentage of help desk incidents fielded from the general public, we found that the agency was, in fact, well above the median.

The concept of best practices can be useful, if properly understood and applied with judgment. Certainly, in terms of how to do business, organizations can learn from one another. Moreover, in terms of measurements, it is quite useful to have a sense for what levels of performance are achieved by peer organizations, or even by organizations outside of one’s own industry.

But in both cases, there’s no magic formula.